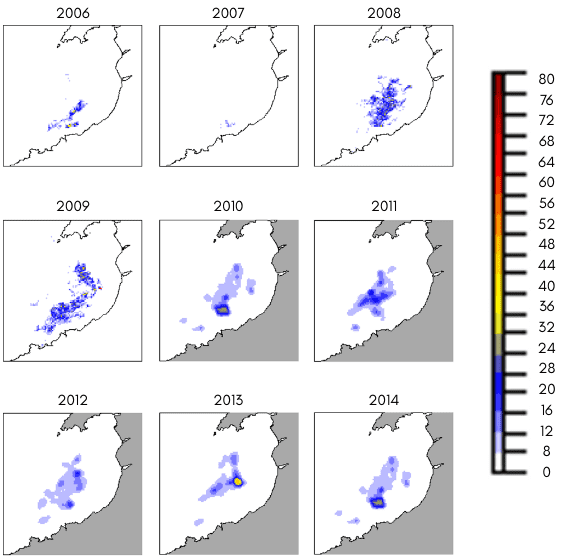

Incidental Catches

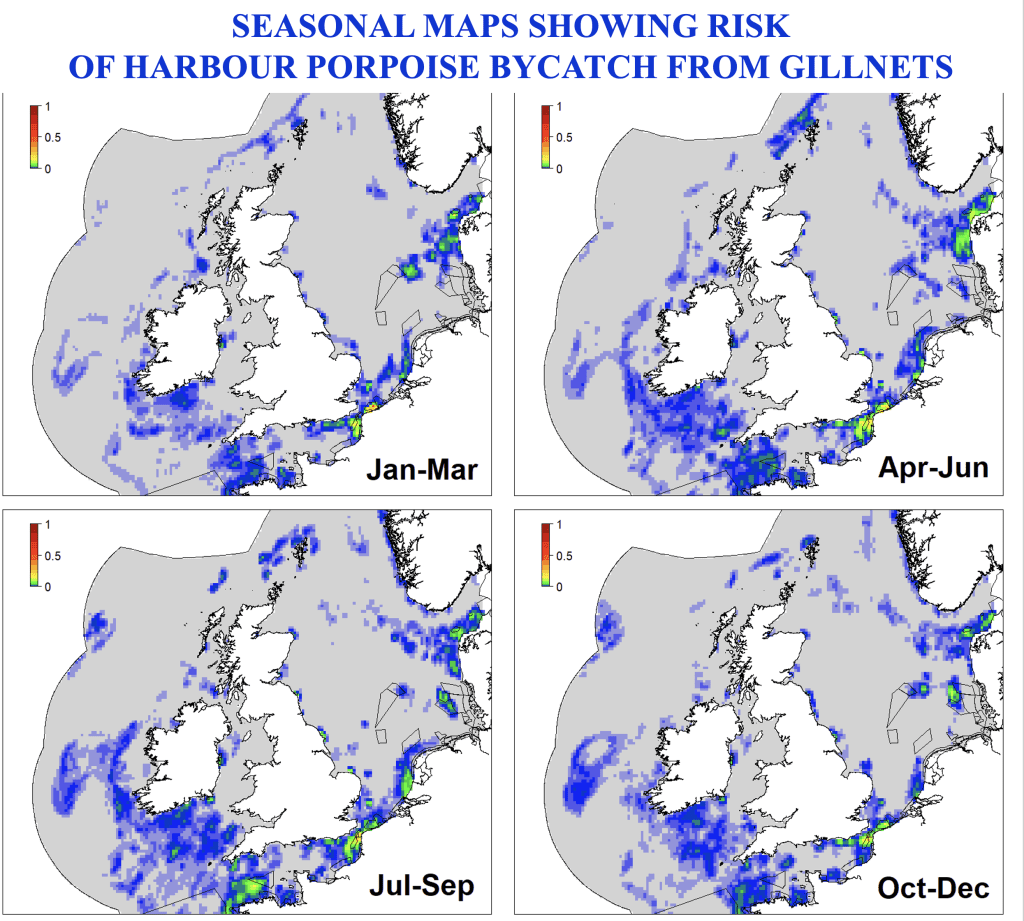

The greatest known cause of human-related mortality for cetaceans in Europe is bycatch – the incidental entanglement of animals in fishing gear. During the 1990s, an estimated 10,000+ porpoises were estimated to die annually in bottom-set gill nets in the Celtic and North Seas whilst in the Western Approaches to the English Channel, large numbers of common dolphins were drowning in trawl fisheries, particularly those targeting sea bass. Fishing effort in the North Sea has declined in recent years but, nevertheless, an estimated 7,000+ porpoises continue to die each year off the coast of west Denmark, in the German Bight, and the eastern Channel. The sea bass fishery has been regulated but common dolphins are now dying annually in their thousands in the northern Bay of Biscay.

Images: 1) Harbour Porpoise, photo credit: F Hobson); 2) Atlantic White-sided Dolphin, photo credit: P Watkinson; 3) Minke Whale, photo credit: R Dyer; 4) Grey seal, photo credit: BDMLR; 5) Harbour Porpoise bycatch risk maps

Over fishing

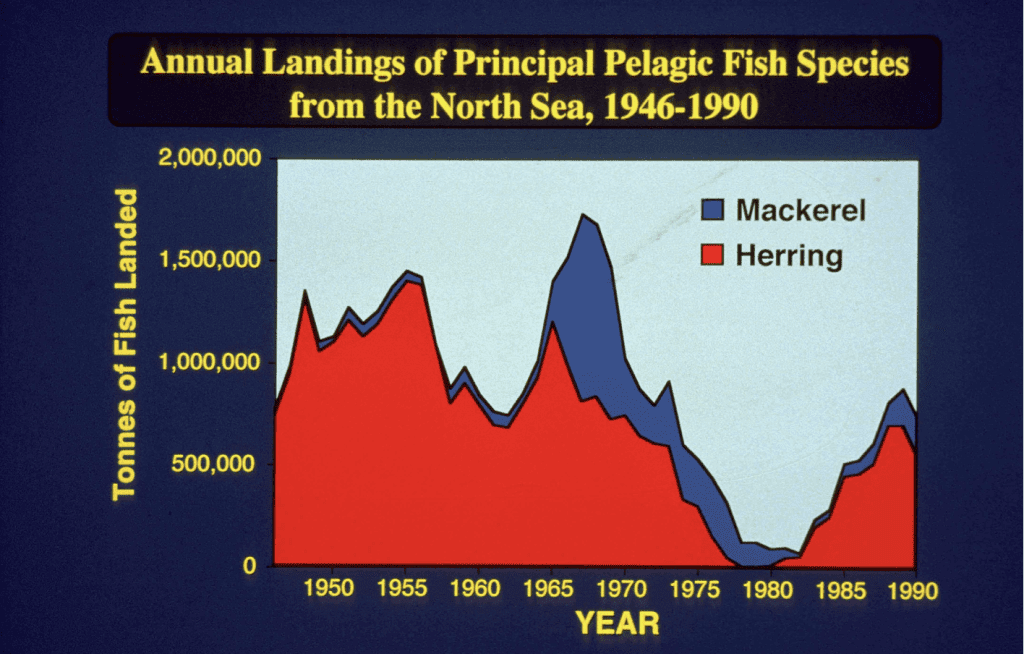

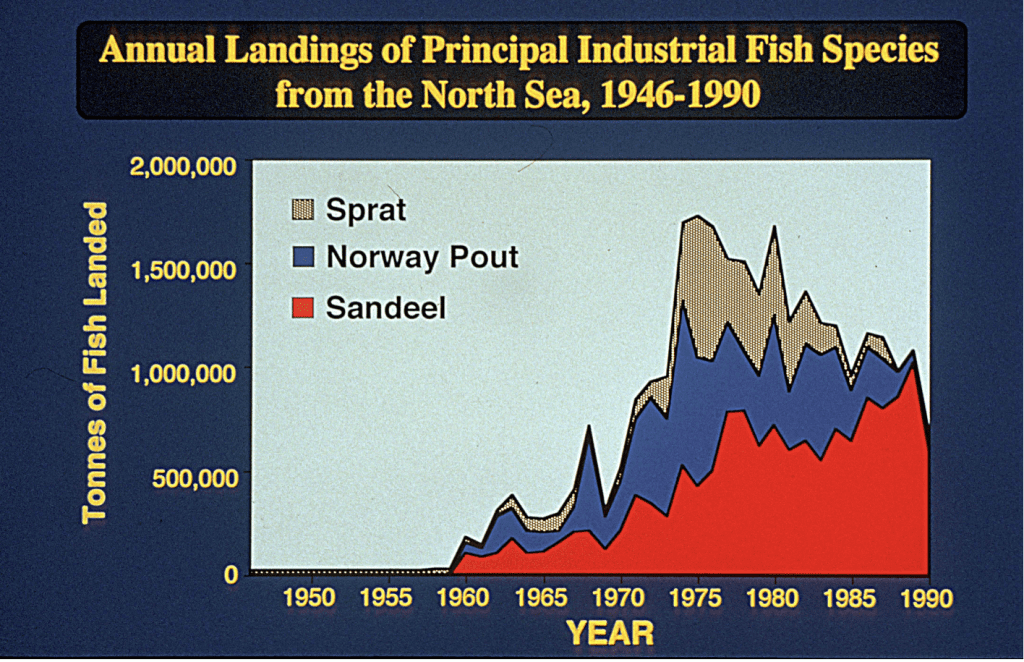

Fisheries themselves can have a major impact upon the status and distribution of various UK cetaceans. Local stocks of several fish species have shown marked declines over the last half century. First it was herring and mackerel in the 1960s and 1970s, then it was sprat and sandeel in the 1980s and 1990s, and in recent times, cod, whiting, sole, and plaice have also all experienced declines in part due to overfishing. All of these fish species are an important food source for several cetacean species.

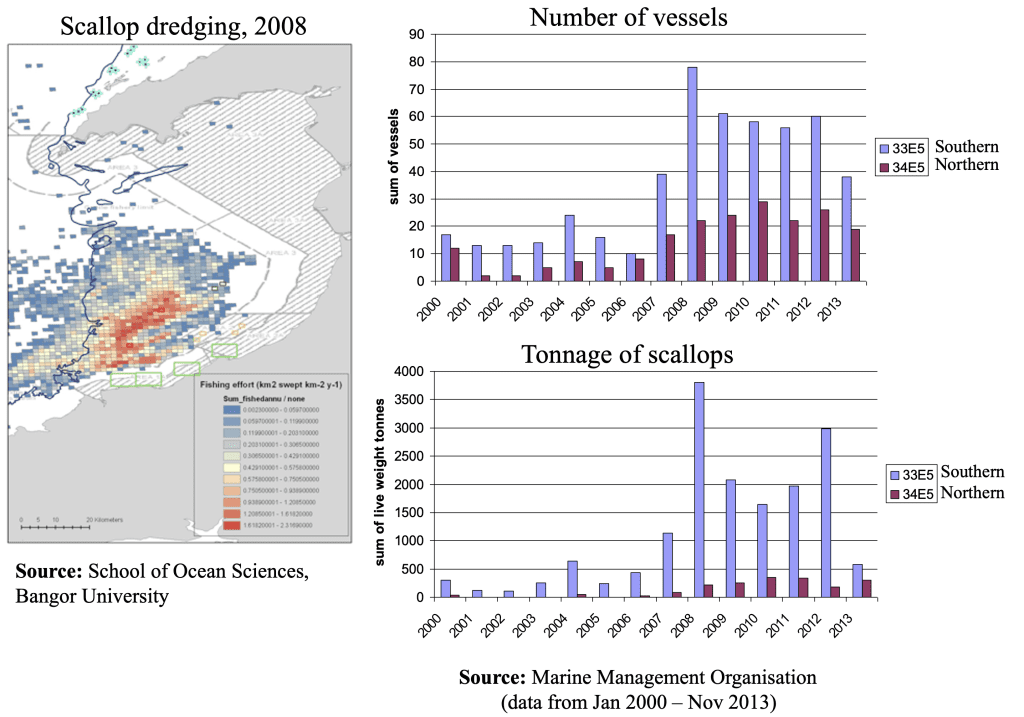

Images: 1) Declines in Herring & Mackerel landings; 2) Increases then declines in Sprat, Norway Pout & Sandeel landings; 3) Increase in Scallop dredging in Cardigan Bay; 4) Areas where bottom dredging for scallops was most intense; 5) Trawler

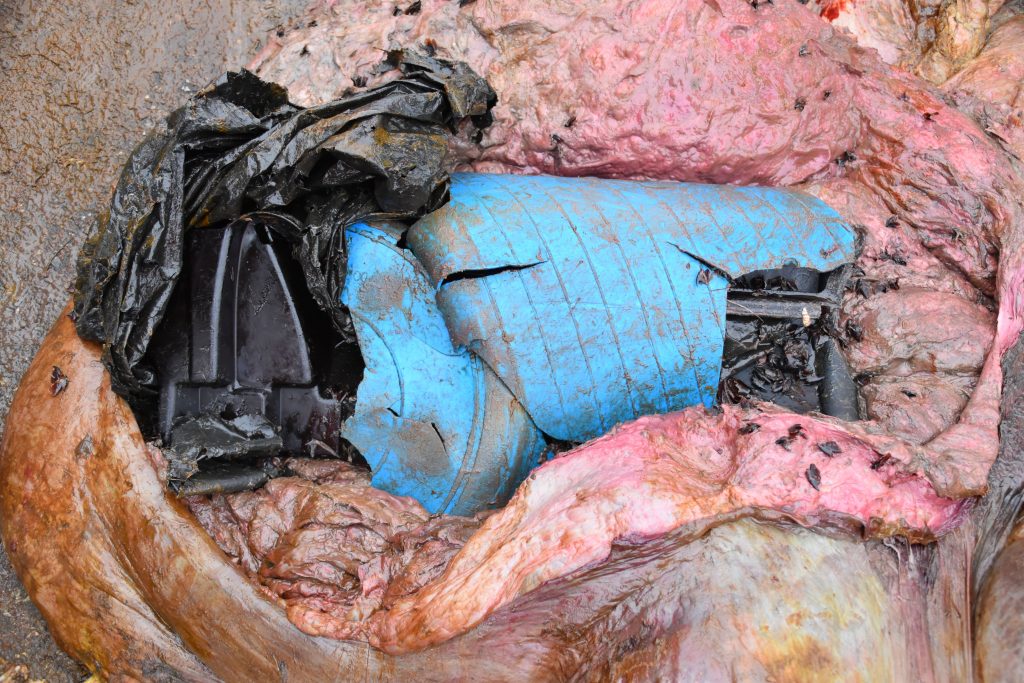

Pollution

As industrial activities continue to develop along European seaboards, pollutants enter the sea and build up in the marine ecosystems. Organochlorine chemicals and some heavy metals can persist in the food chain for long periods of time, often stored in an inert state in the blubber of marine mammals. Concentrations build up as large predators like whales and dolphins feed upon contaminated prey, and pollutants are passed directly from one generation to the next through the placenta or the mother’s milk. Porpoises, bottlenose dolphins and killer whales all have levels of PCB (polychlorinated biphenyls) contaminants that generally exceed those known to cause negative effects such as endocrine disruption leading to reproductive failure and reduced immunity to infectious diseases.

Images: 1) Industrial pollution; 2) Industry in Liverpool Bay; 3) Plastic Debris in Sperm Whale stomach; 4) Beach Pollution; 5) Plastic being collected from beach

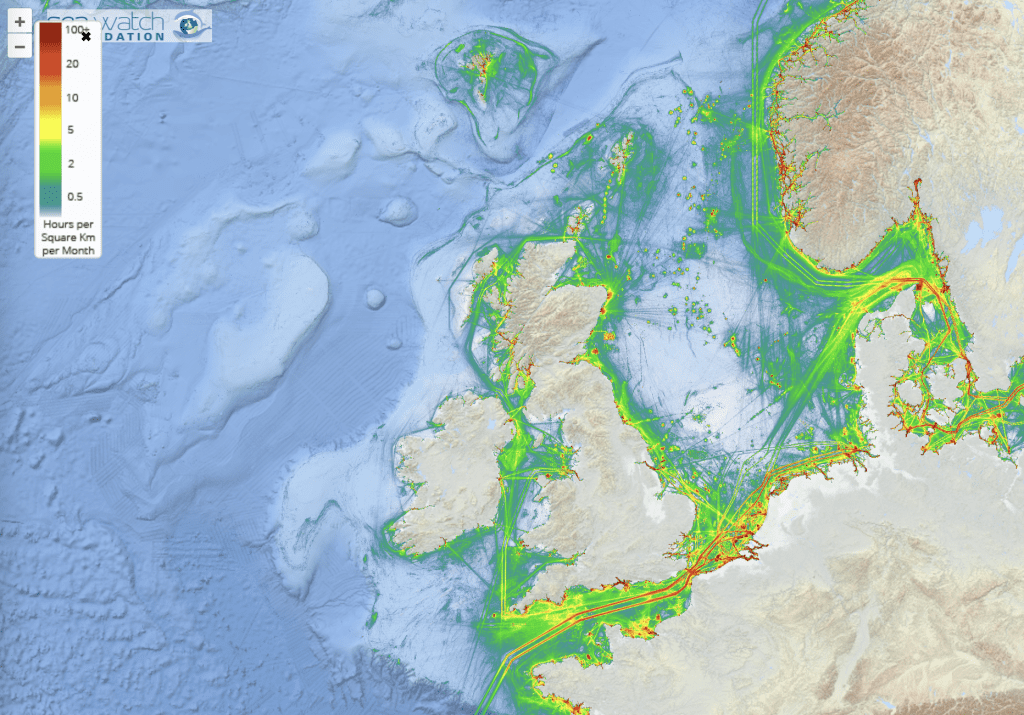

Underwater Noise

Marine mammal species are being exposed to an increasing amount of noise pollution in shelf seas. Marine traffic around parts of the British Isles is amongst the most intense of anywhere in the world, the North Sea alone receiving more than half a million ship movements a year. Seismic exploration for oil and gas extended to cetacean rich waters west of Scotland and Ireland with intense low frequency sounds posing a threat, particularly to baleen whales. Pile driving activities used in the construction of offshore wind farms have been shown to exclude porpoises over large areas and extended periods of time that may number several years. The use of mid-frequency long-range active sonar by the military has been shown to cause mass strandings of beaked whales in the North Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea. In the last three decades, the coastal zone has received increased public attention for recreational purposes with the inevitable consequences of cetaceans having a greater exposure to disturbance from speedboats and other pleasure craft, and the very real possibility of physical damage from collisions.

Images: 1) Pile driving during windfarm construction; 2) 3-D seismic survey vessel; 3) Exploding military ordnance; 4) Military vessel carrying mid-frequency sonar; 5) Map of shipping traffic

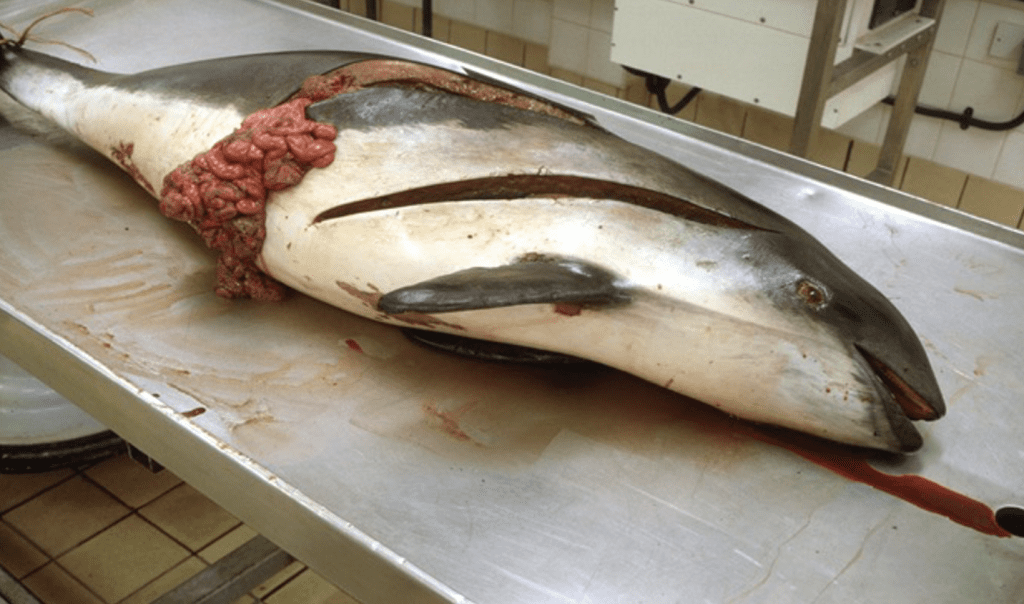

Disturbance

The presence of vessels around cetaceans is fast becoming a threat to cetaceans and other marine wildlife. Recreational activities in the coastal zone are popular in many parts of Europe, as an increasing number of people possess speedboats, jet skis and other personal watercraft. Vessels, particularly fast-moving ones, pose dangers of physical strikes either from their hard hulls or their sharp propellers. They can also generate underwater noise that can mask communication, or in some cases if the sounds are loud enough, damage hearing. The result is that cetaceans often respond negatively to vessels particularly if they approach the animals rapidly. They may change their dive behaviour and move away from them, and this can lead to the disruption of social groups and reduced feeding by individuals which reduces their energy intake and can affect survival and reproduction.

Images: 1) Boats disturbing bottlenose dolphins; 2) Jet skis; 3) Speedboat; 4) Bottlenose dolphin vessel strike victim; 5) Harbour porpoise with propeller cut, photo credit: CSIP

Climate Change

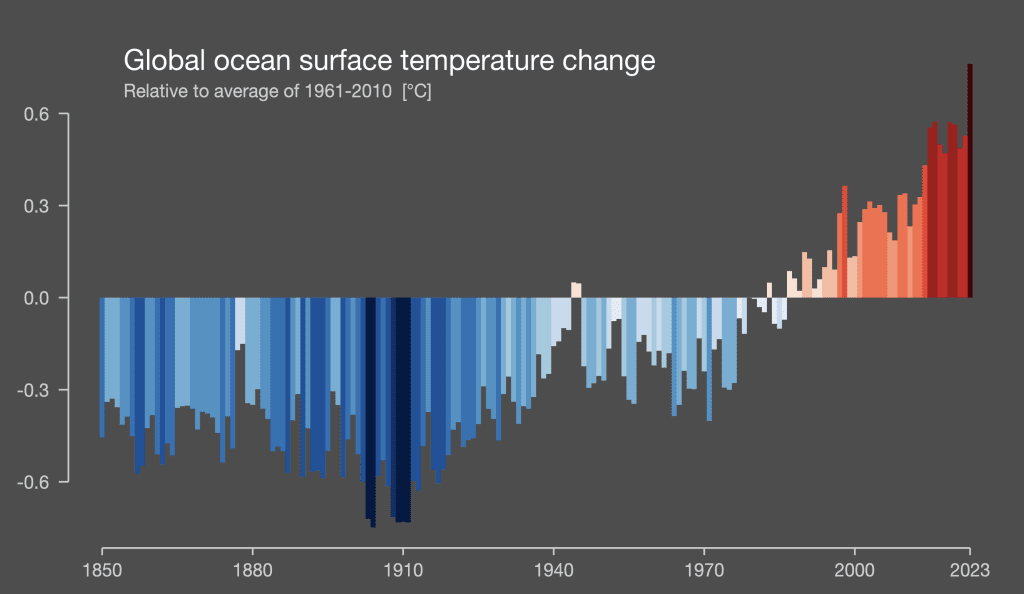

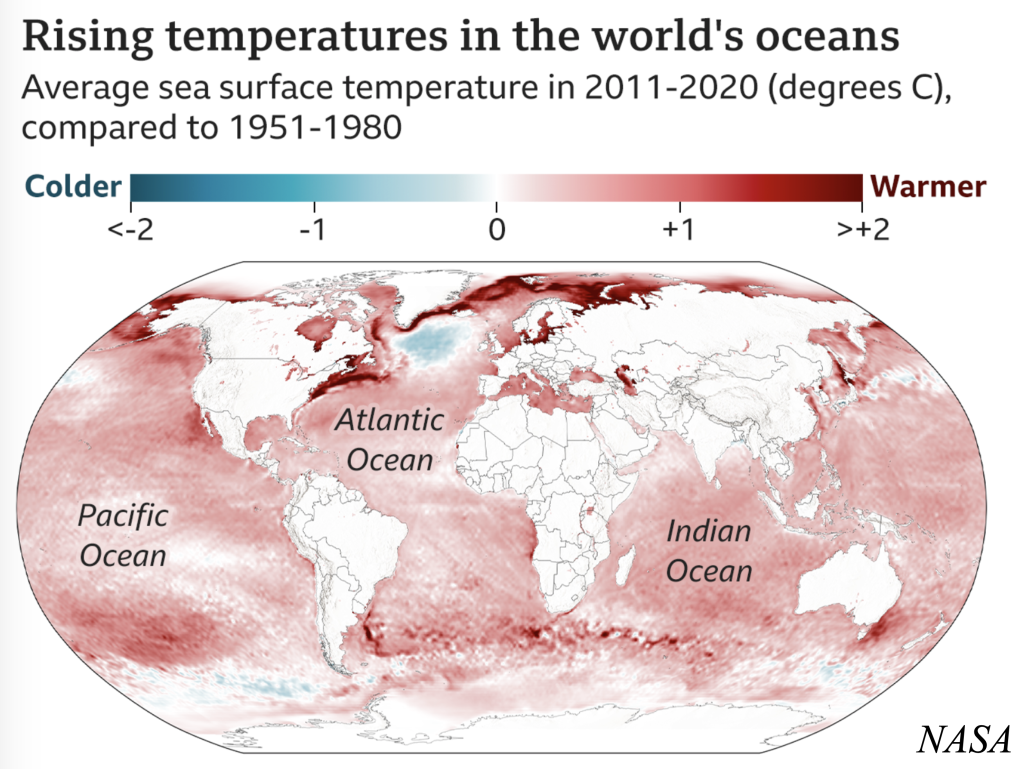

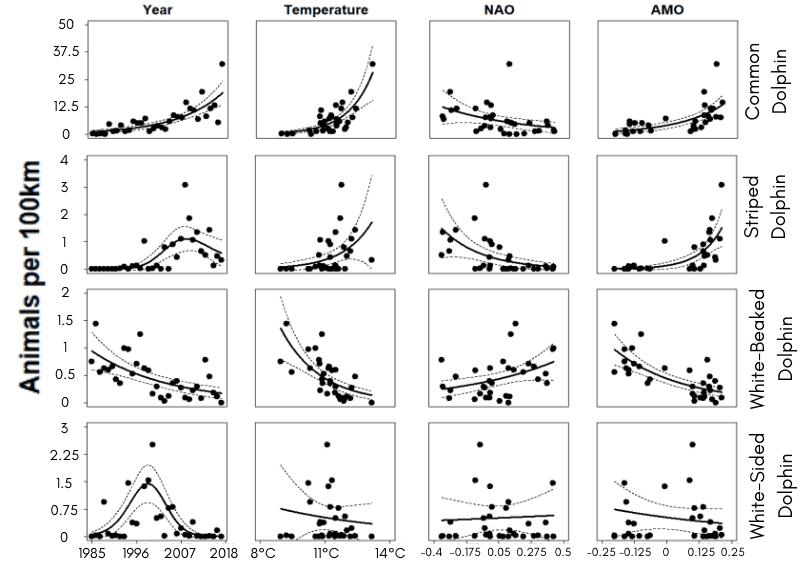

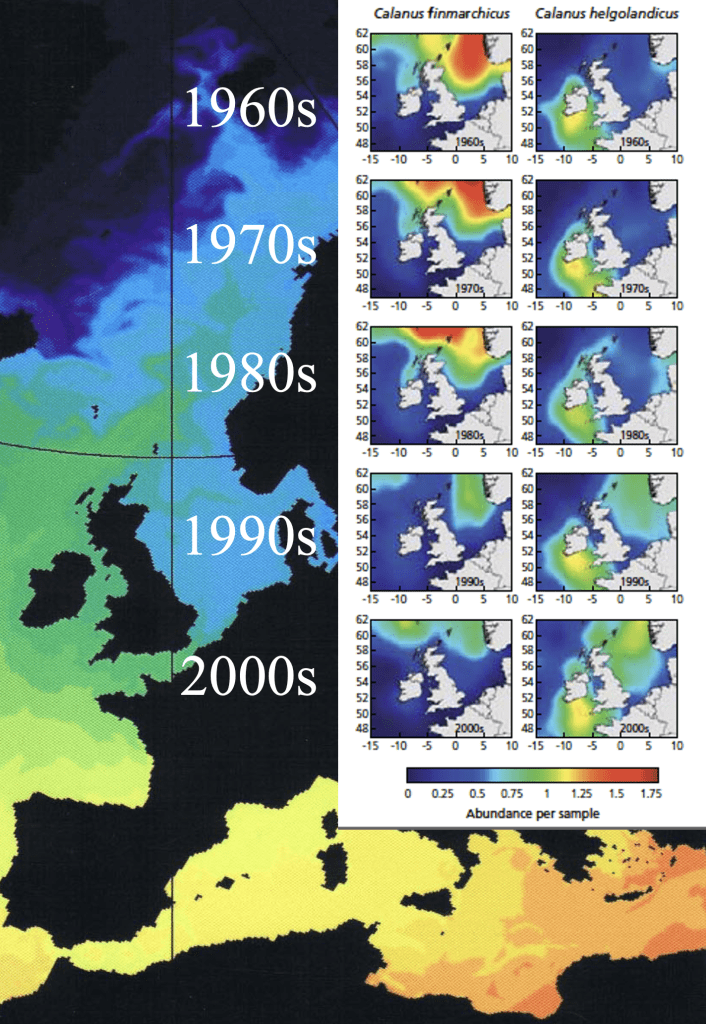

Climate change due to anthropogenic causes poses several possible threats to cetaceans. Obvious consequences will be the increase in sea temperature and the subsequent melting of polar ice and drowning of coastal plains, along with changes in levels of primary productivity, which could severely affect the prey distribution of marine mammals. Other less direct implications include an increase in the frequency and velocity of storms; severe storm events could cause substantial physical damage to habitats and species. The distribution of many marine mammal species may be affected by the shifts in areas of primary productivity and prey distribution caused by climate change. In the UK, warmer water species such as striped dolphin and Cuvier’s beaked whale are occurring more frequently on the west coast and common dolphins into the northern North Sea whereas Atlantic white-sided and white-beaked dolphins may be shifting their range northwards. Some species, such as land-breeding pinnipeds and coastal cetaceans, may find it difficult to adjust to the loss of important feeding or breeding habitat due to changing temperatures. On a global scale, predictions are that cold-water species will shift towards the poles and therefore result in the reduction of their global range.

Images: 1) Global increase in sea temperatures; 2) Global variation in sea temperature rises; 3) Effects of Year, Sea temperature, North Atlantic Oscillations, and Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillations on the densities of four cetacean species in European Seas; 4) Planktonic changes over time; 5) Polar Bear – a victim of climate change

Hunting

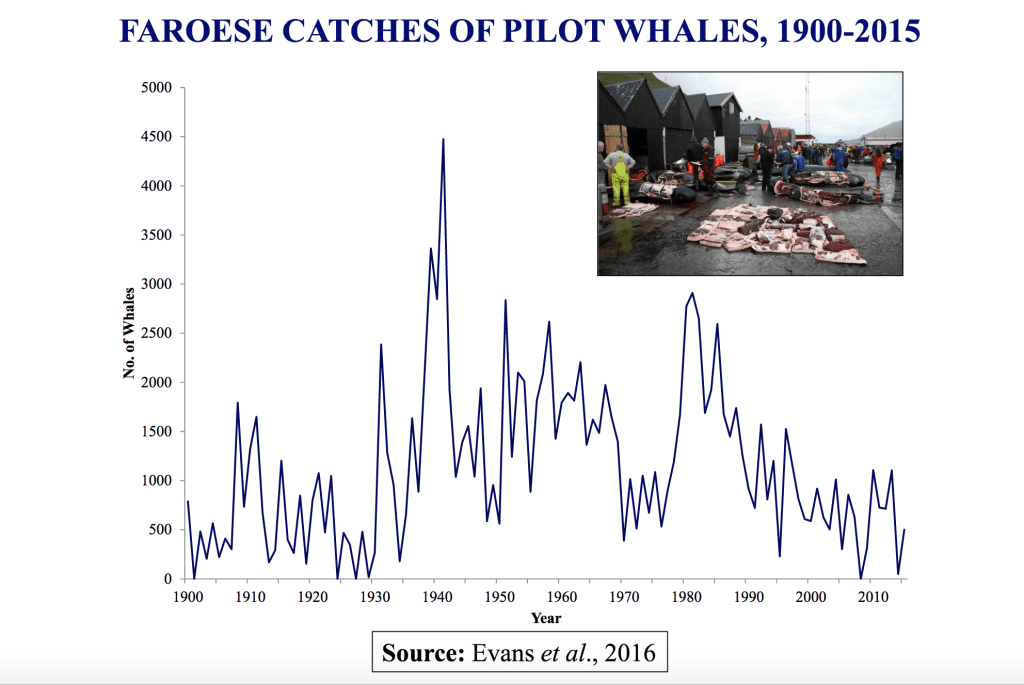

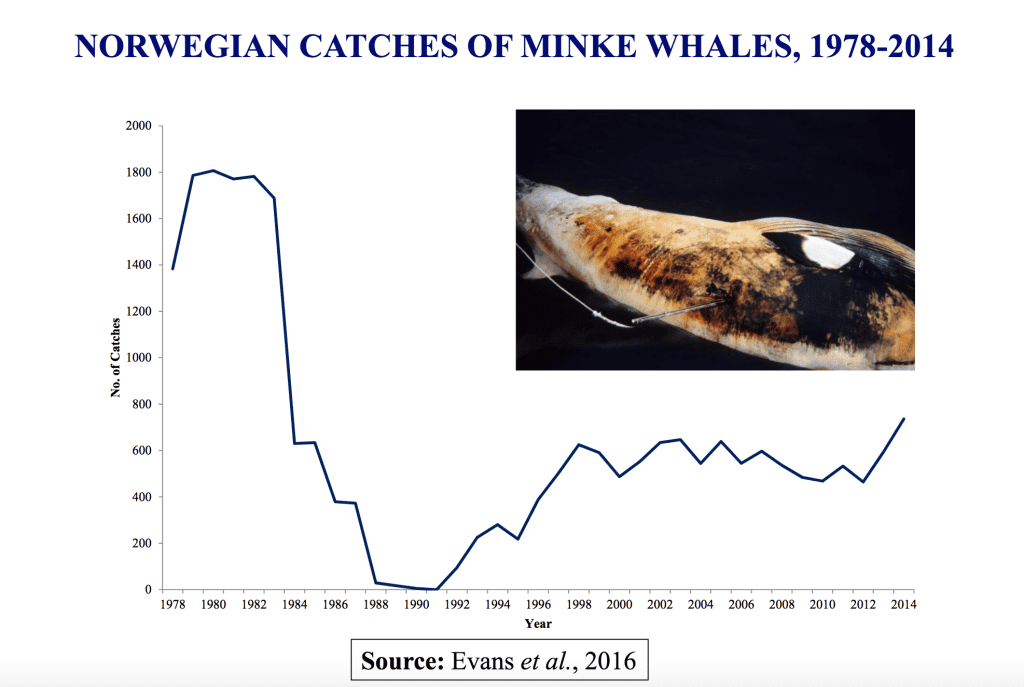

Most of the great whales of the world’s oceans were reduced to near extinction by centuries of hunting, with Britain being one of the countries leading the way in causing the demise of these animals. As recently as the late 1920s, there were active whaling stations in Shetland and the Outer Hebrides, and on the west coast of Ireland. Collectively, they killed nearly 10,000 whales in British waters over a period of just fifteen years. Species like the North Atlantic right whale, and blue whale have become very rare in UK waters and the Atlantic gray whale became extinct. Although, after thirty years of protection in the North Atlantic, there are some signs of recovery for species such as humpback whale. The 1990s saw a resumption of hunting in the guise of scientific whaling, with Norway annually taking around 600 minke whales in waters north of Shetland. Iceland resumed commercial whaling, taking around 150 fin whales in 2017 and 2018, but then temporarily ceased whaling. The Faroe Islands continue to kill an average of between around 500 and 1,000 long-finned pilot whales each year, occasionally also taking other species such as Atlantic white-sided dolphin and killer whale.

Images: 1) Pilot whale drive in the Faroes; 2) Numbers off pilot whales taken in the Faroes; 3) Whaling vessel in Iceland, photo credit: Sea Shepherd UK); 4) Flensing a blue-fin whale hybrid in Iceland; 5) Norwegian catches of minke whales