Oct 25, 2025

by Ben Phillips

The ancestors of baleen whales that swam through the Peruvian seas approximately 12 to 13 million years ago likely faced a formidable threat in Livyatan melvillei – a fearsome apex predator with a taste for whale flesh.

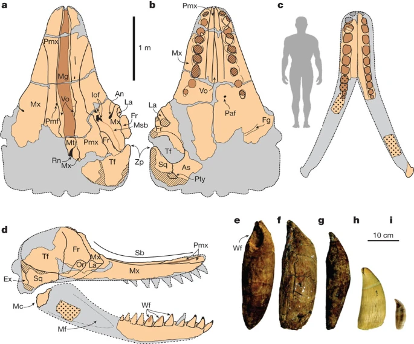

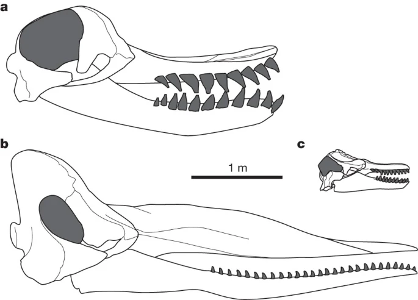

With an estimated body length of 13.5 to 17.5 meters, Livyatan melvillei was similar in size to modern sperm whales. However, it was far more formidable: its massive head, measuring around 3 meters long and 1.9 meters wide, was large enough that this whale could easily swallow a human whole. Livyatan possessed enormous teeth, up to 12 cm in diameter and 36 cm in length, more than twice the length of those of Tyrannosaurus rex. That makes them the largest known non-tusk teeth ever recorded. These teeth were set in a pair of wide, robust jaws capable of delivering a formidable bite. In contrast, modern sperm whales have much smaller teeth – over 40% shorter – confined to their narrow lower jaw and used primarily for social interactions. Today’s sperm whales are deep-diving suction feeders, preying mainly on squid, which they draw into their mouths rather than grasping with teeth.

But Livyatan was no suction feeder – its teeth reveal a powerful, macroraptorial whale adapted to hunting large prey. Deeply embedded in the jaw, the teeth could withstand immense pressure during hunts. Their interlocking design helped secure prey, preventing escape, while their forward-angled orientation suggests an adaptation for grasping curved-bodied marine animals – such as other whales. Livyatan’s short, broad snout enabled its front teeth to clamp down with tremendous force, and its large temporal fossa (see Figure 2) housed exceptionally strong jaw muscles capable of delivering a formidable bite – likely the most powerful of any tetrapod. Tooth wear patterns indicate that the teeth sheared past one another when biting, allowing Livyatan to tear off large chunks of flesh. This hunting technique is still seen in modern killer whales, though on a smaller scale. Preying on other whales would have provided Livyatan with the energy needed to sustain its enormous size.

The concave shape of Livyatan’s skull suggests it possessed a melon and a spermaceti organ, similar to those found in modern sperm whales. While the exact function of the spermaceti organ remains uncertain, it is thought to play a role in buoyancy regulation during deep dives. However, since Livyatan likely did not hunt squid or dive to great depths like modern sperm whales, other theories have been proposed. One such idea is that the organ functioned as a battering ram during intraspecific combat. It may have also enhanced echolocation, potentially enabling Livyatan to stun prey with sound or attract mates – especially considering that male sperm whales have a larger spermaceti organ.

Many factors could have contributed to Livyatan’s extinction. One major cause was global climate cooling toward the end of the Miocene epoch (approximately 23 to 5.3 million years ago), which likely impacted ocean ecosystems. This cooling may have led to a decline in the diversity, distribution, and size of baleen whales – the primary prey of Livyatan. Livyatan likely inhabited the seas off South America alongside the giant shark Megalodon, and the two apex predators may have competed for similar prey. In addition, the ancestors of modern orcas began to diversify during this period and may have been more efficient or adaptable hunters, potentially outcompeting Livyatan for food resources.

Regardless of how Livyatan went extinct, it likely played a significant role in shaping Miocene marine ecosystems. Through the study and conservation of its closest living relative, the modern sperm whale, we can continue to uncover insights into Livyatan’s biology and evolutionary history.