Anthropogenic activities are impacting nature on a global scale (Storch et al., 2021), placing ecosystems under immense pressure. The world’s oceans are amongst the most heavily affected, under pressure from overexploitation, climate change, and pollution (Halpern et al., 2019; Link, 2021; Thiagarajan, 2025). The cumultive impact of these threats has been recognised worldwide, prompting implementation of policies to protect and restore marine ecosystems. These include the sustainable management of depleted fish stocks, expansion of marine protected areas, and international agreements such as the Paris Agreement, which aims to limit ocean warming by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Yet human influence on marine environments extends back centuries (Hoffmann, 2004), beginning long before modern monitoring or conservation was established.

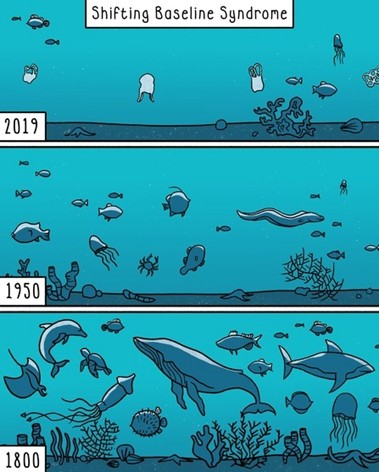

Restoring marine ecosystems to a healthy state is a complex challenge. Defining what “healthy” means, deciding which baseline should guide restoration targets, and determining the characteristics of a successfully restored system are all critical considerations. Furthermore, societal perceptions of what is considered “normal” shift as degradation continues. This phenomenon was first described by fisheries scientist Daniel Pauly, termed the “shifting baseline syndrome”. This refers to the tendency of each generation to perceive the environment of their youth as natural (Pauly, 1995). Over time, as the environment is further degraded, each new state becomes the new normal. In other words, the baseline shifts.

Several factors contribute to shifting baselines, including generational amnesia, the loss of historical ecological knowledge, and limitations in long-term data availability (Papworth et al., 2009; Soga & Gaston, 2018). Generational amnesia occurs when each generation normalises the conditions of their youth (Pauly, 1995; Papworth et al., 2009), meaning progressively degraded ecosystems appear acceptable. Related is the loss of historical knowledge, as traditional knowledge, oral histories, and cultural memories fade over time (Papworth et al., 2009). Without this information, past ecosystem states are challenging— if not impossible — to reconstruct, although studies show that integrating these perspectives can aid with recovery (McClenachan et al., 2012). Finally, limitations in long-term ecological data contribute to shifting baselines as scientific monitoring typically only spans recent decades (Soga & Gaston, 2018). Yet human impacts on marine ecosystems stretch back centuries, as evidenced by historical and archaeological analyses of reefs and fish (Pandolfi et al., 2003; Thurstan & Roberts, 2010).

The consequences of shifting baselines for conservation and management are profound. Normalisation of degraded states can reduce the urgency and ambition of restoration, leading to the acceptance of diminished ecosystems as adequate (Soga & Gaston, 2018; Alleway et al., 2023). Shifting baselines can also foster intergenerational differences in perception, with different age groups holding contrasting views on what constitutes a “healthy” ecosystem, further complicating conservation goals (Soga & Gaston, 2018). Ultimately, the failure to recognise long-term ecological change risks lowering societal expectations of nature, reinforcing a cycle in which progressively degraded states are increasingly accepted as the norm (Alleway et al., 2023). The causes and consequences of shifting baselnes are not only theoretical but are evident in real-world marine ecosystems. Fisheries and coral reefs provide two particularly well-documented examples, illustrating how degraded conditions have been normalised, reinforcing conservation complacency and complicating restoration goals.

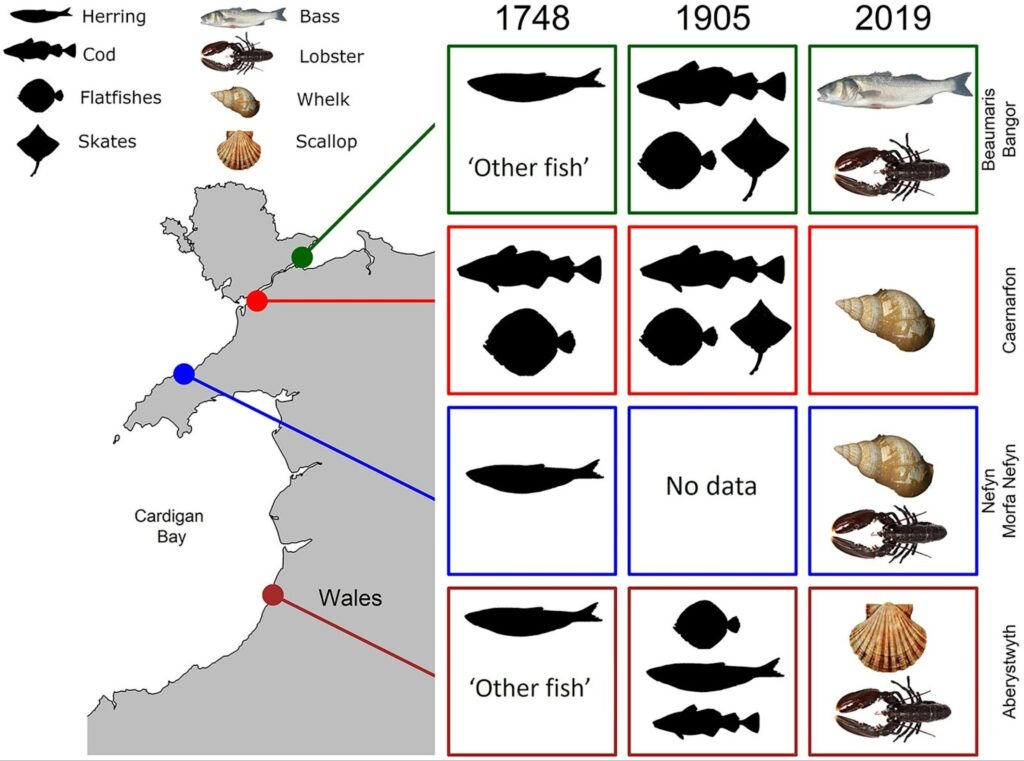

Moore et al. (2024) use diverse qualitative historical sources — including fisheries reports, naturalists’ accounts, and recipes — to reconstruct century-scale changes in fisheries in the Irish Sea. Their findings revealed the collapse of the centuries-old pelagic herring fishery, alongside the disappearance of multi-species demersal and intertidal fisheries. Numerous taxa — including crusteceans, elasmobranchs, sturgeons, and teleosts — have undergone local, commercial, or functional extinction, representing major ecological losses. Today, fisheries in the region rely heavily upon few shellfish species (Figure 2). By synthesising centuries of diverse sources, the authors highlight the scale of ecological loss on the Welsh coast of the Irish Sea, reducing the risk of shifting baselines by extending knowledge beyond the limited scientific record.

Coral reefs provide another example of shifting baselines, this time on a global scale. Pandolfi et al. (2003) combined palaeoecological, archaeological, and historical evidence to show that reef degradation began centuries ago, long before systematic scientific monitoring. Populations of large reef fauna — including marine turtles, manatees, and predatory fish — were reduced by early overfishing and local exploitation, triggering cascading effects on reef structure and functioning. Because widespread surveys only began in the mid-20th century, these depleted conditions were often accepted as natural baselines. Even the best-protected reef system, the Great Barrier Reef (GBR), is estimated to be only one-quarter to one-third of the way towards ecological extinction, with nearby Moreton Bay showing comparable degradation to other reefs worldwide. And this is before the added impacts of modern threats such as coral bleaching and disease. Together, these examples highlight how even “pristine” systems like the GBR have long been in decline, yet continue to be perceived as relatively untouched. As a result, reliance on truncated baselines obscures the true scale of ecological loss and risks setting restoration targets far below what is required to return reefs to a genuinely healthy state.

Shifting baselines illustrate how perceptions of what is “natural” or “healthy” can differ dramatically from reality. This can have profound consequences for conservation and restoration. As illustrated by Welsh fisheries and coral reefs worldwide, without considering historical sources there is a risk of normalising degraded ecosystems, lowering expectations, and limiting conservation and restoration ambition. Recognising and addressing shifting baselines is therefore critical — by combining historical data, traditional knowledge, and long-term monitoring, we can better understand past ecosystems, set more meaningful restoration targets, and ensure that conservation efforts aspire to recovery rather than persistence.

References

Moore, A., et al. (2024). Century‐scale loss and change in the fishes and fisheries of a temperate marine ecosystem revealed by qualitative historical sources. Fish and Fisheries, 25(5).

Alleway, H.K., et al. (2023). The shifting baseline syndrome as a connective concept for more informed and just responses to global environmental change. British Ecological Society, 5(3).

Halpern, B.S., et al. (2019). Recent pace of change in human impact on the world’s ocean. Scientific Reports, 9(1).

Hoffmann, R.C. (2004). A brief history of aquatic resource use in medieval Europe. Helgoland Marine Research, 59(1).

Link, J.S. (2021). Evidence of ecosystem overfishing in U.S. large marine ecosystems. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 78(9).

McClenachan, L., et al. (2012). From archives to conservation: why historical data are needed to set baselines for marine animals and ecosystems. Conservation Letters, 5(5).

Okrondu, J., et al. (2022). Anthropogenic Activities as Primary Drivers of Environmental Pollution and Loss of Biodiversity: A Review. International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development, 6(4).

Pandolfi, J.M. (2003). Global Trajectories of the Long-Term Decline of Coral Reef Ecosystems. Science, 301(5635).

Papworth, S.K., et al. (2009). Evidence for shifting baseline syndrome in conservation. Conservation Letters, 2(2).

Pauly, D. (2022). Daniel Pauly (1995). Cambridge University Press eBooks.

Soga, M. and Gaston, K.J. (2018). Shifting baseline syndrome: causes, consequences, and implications. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 16(4).

Storch, D., et al. (2021). Biodiversity dynamics in the Anthropocene: how human activities change equilibria of species richness. Ecography, 2022(4).

Thiagarajan, C. and Devarajan, Y. (2024). The Urgent Challenge of Ocean Pollution: Impacts on Marine Biodiversity and Human Health. Regional Studies in Marine Science, 81(103995).

Thurstan, R.H. and Roberts, C.M. (2010). Ecological Meltdown in the Firth of Clyde, Scotland: Two Centuries of Change in a Coastal Marine Ecosystem. PLoS ONE, 5(7).