Mar 11, 2021

By: Lucy

When we think about UK cetaceans, most of us imagine a leaping dolphin or rolling porpoise. But with over 30 species inhabiting UK waters, it’s easy to forget the diversity that surrounds us. The Sea Watch Foundation database currently holds 23,134 sightings of bottlenose dolphins since 2007, averaging a staggering 1,652 sightings per year. Comparatively, there are just 94 sightings of beaked whale species in the same time period! And yet, the group of cetaceans we know the least about might just be one of the most interesting: record-breaking dives, unusual feeding strategies, and tusks-for-teeth are just some of the characteristics that make this group of animals so enigmatic. So, let’s take a deep dive…

There are currently about 22 recognised species of beaked whale worldwide, belonging to six genera. Only three to four of these are well-described, and even then, information is patchy. All beaked whales belong to the Suborder Odontoceti, as they possess teeth (though not in the way we’d expect!), and the family Ziphiidae. Generally, beaked whales are small to medium in size, and all possess a distinctive, elongated ‘beak’ which lends them their name. All species possess a very similar body profile, with small dorsal flippers, triangular dorsal fins, a bulging ‘melon’, and tail flukes that lack a dividing notch. With only subtle differences in their beaks, colouration, and surface pattern, positively identifying beaked whales is a challenge (Mead, 2009; MacLeod, 2018).

“The group of cetaceans we know the least about might just be one of the most interesting”.

As a result, new species are discovered relatively frequently – in 2019, the new species Berardius minimus was described in Japan (Yamada et al. 2019), and last year a suspected new species was photographed in Mexico (BBC 2020). Beaked whales are one of the most geographically widespread cetaceans but are generally restricted to occupying deep offshore waters and their relative numbers are unknown.

All species within the Odontoceti suborder have teeth, but beaked whales are unique in that they only possess one or two pairs (with the exception of the Shepherd’s beaked whale) (Mead. 2009).

Interestingly, rather than being a tool for feeding, they function as a secondary sexual characteristic – these tusk-like teeth only erupt through the jaw in males and are used in combat over access to females, much like how deer battle using their antlers (Dalebout et al. 2008). Considering females never develop teeth, and males use them for another purpose, how do these toothed whales eat?

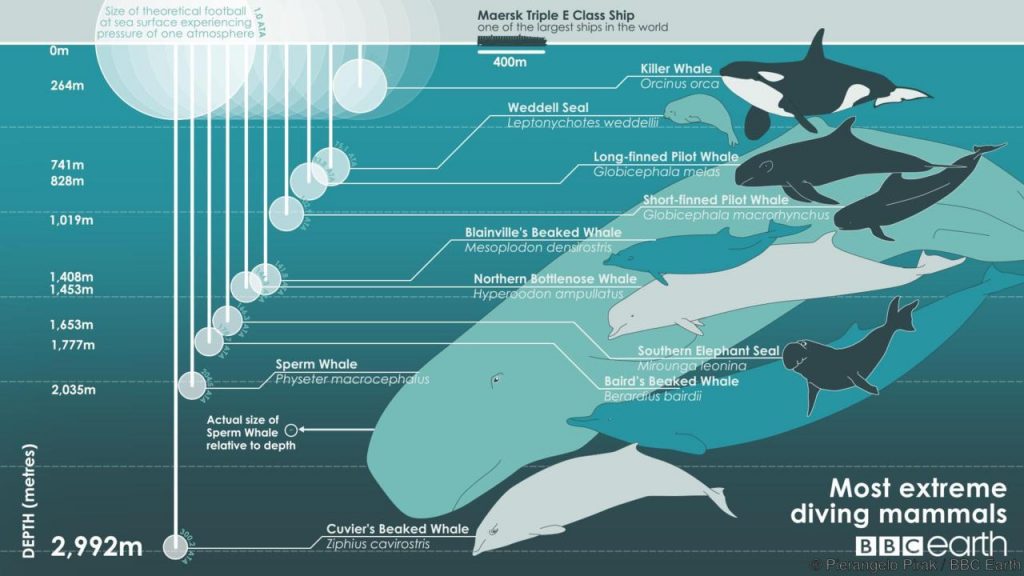

“This leads us to perhaps the most impressive feature of beaked whale ecology and behaviour – beaked whales hold the record for the longest, deepest dives of any mammal”.

Beaked whales echolocate to find food, and their diets are thought to consist mainly of deep-water squid, crustaceans, and benthic fish (Pereira et al. 2011; West et al. 2017). With the absence of teeth, beaked whales feed using suction. This is a method that is also found in other odontocete (and some mysticete) species, whereby characteristic grooves in the animal’s throat expand, causing the changing pressure inside the mouth to force intake of water and prey (Johnston & Berta, 2010). This leads us to perhaps the most impressive feature of beaked whale ecology and behaviour – beaked whales hold the record for the longest, deepest dives of any mammal. Amazingly, beaked whales have been recorded diving almost two miles below the surface, for periods of over three hours! (Schorr et al. 2014; Quick et al. 2020). More regularly, beaked whales dive 500m or below in search of food for periods of about an hour.

To achieve this, beaked whales are uniquely adapted to extreme diving behaviour. To withstand such dives, their bodies must optimise their oxygen stores and cope with a build-up of lactic acid (Tyack et al., 2006). Physiologically, their heart rate slows, blood flow is targeted to essential tissues, and their lungs fully collapse. This ensures oxygen is still available to essential tissues and prevents the exchange of gasses between the lungs and the blood, which reduces the likelihood of dangerous nitrogen build-up in tissues. Anatomically, beaked whales have unusually large spleens and livers when compared to other cetacean species, which may increase the ability of the body to effectively rid itself of toxins associated with prolonged oxygen starvation. They are also incredibly streamlined animals, possessing slight depressions in their body wall that allow their pectoral fins to lie flush to their sides, which reduces the energetic cost of diving (Rommel et al., 2006).

Like many other cetacean species, beaked whales are at risk from a number of anthropogenic pressures. These are becoming ever more prevalent as human pressures start to encroach on their deep, offshore marine habitat, that were previously inaccessible. One of the main risks to beaked whales is noise, as unexpected sound (e.g., from sonar activity) can panic diving whales and cause them to return to the surface rapidly, which effectively induces decompression sickness (Zimmer & Tyack 2007). Their diving behaviour means they have little ability to avoid noise once engaged in a dive. Previous mass stranding events have been linked to sonar use (Parsons 2017), and this is thought to have been the cause of a number of beaked whale strandings in the UK in 2018. Other risks to beaked whales include the ingestion of microplastics, or chemical contamination via persistent organic pollutants. For example, a study published last year that sampled 20% of a Cuvier’s beaked whale population in the Mediterranean Sea, found 80% of individuals were over the accepted threshold for chemical contamination (Baini et al. 2020). These risks are only now becoming better understood with more advanced technology for sampling and new methods for investigating the health of stranded animals (Lusher et al. 2015).

Whilst our knowledge of this group is ever-growing, beaked whales remain one of the least understood groups of animals in the world – so every record and sighting is important in the quest to understand more about their ecology, life-history, and conservation status. Who knows what else we will discover about this mysterious group? To learn more about the topics in this blog, check out our recent featured blog on marine noise or check out our species fact sheets for more information on our better-known beaked whale species! And finally…

Lucy

Sea Watch Foundation volunteer

Feature Blogger

Sources

Mead, J. (2009). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. 2nd ed. Academic Press, pp.94-97.

MacLeod, C. (2018). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. 3rd ed. Academic Press, pp.80-83.

BBC News. (2020). ‘New’ whale species seen off Mexican coast.

Zimmer, W. and Tyack, P. (2007). Repetitive shallow dives pose decompression risk in deep-diving beaked whales. Marine Mammal Science, 23(4), pp.888-925.